So Sarah Palin, the President of the United States, which was subject to repossession by China, enacted the “Word Tax” to keep the White House from going into foreclosure. Citizens living inside all city limits were taxed for both spoken and written word. This was tracked by a “Freedom Chip” which was implanted in the back of the neck. The procedure was mandatory and often performed at veterinary clinics. Only politicians and pornographers could afford to be treated by human doctors. Folks didn’t appreciate being treated like animals, but under the “New Patriot Act,” complaining was deemed a commodity, and thus taxable. Someone suffering a broken arm or stroke had to wait while, say, a guinea pig had a marble surgically removed from its anus.

The only folks that survived in the real world were the Field Dwellers. A Field Dweller was someone who lived in the country. Everyone was required to receive a Freedom Chip, but it wasn’t directly enforced. Those without Freedom Chips were considered “Persons with Non-Competencies.” The tax man could shut off your phone, internet, lights, whatever, but they didn’t come looking for you. Like most people, they were scared of the real world. Aside from bullying folks on social media, digital bank accounts or email, they were as harmless as housecats.

Technology helped us think beyond our brains, but the information slowly dried up. “Selectively cleansed,” claimed the government, but that didn’t keep folks from depending on it.

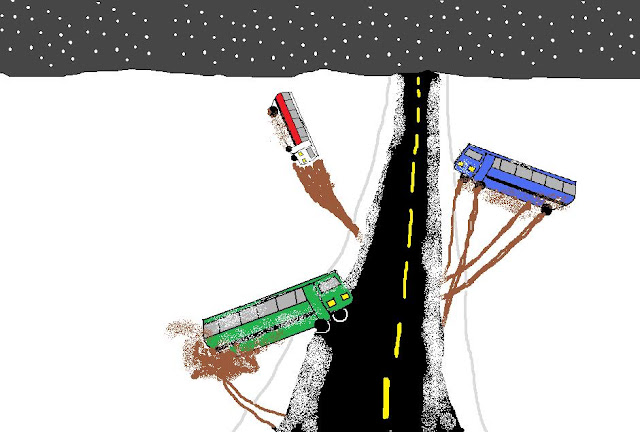

My days, I decided, were numbered. After receiving the letter from Brigadoon Animal Hospital informing me of my Freedom Chip appointment, I left town. After packing a suitcase, I drove South using back-country roads and spent the night in my car. The next morning, I remembered something from my childhood: a trailer colony in the middle of a dirt farm. Growing up, our family used to pass it when we took the short cut to Raleigh. I’d look out the window of our Chevy Blazer, surrounded by soy bean and cotton fields, before coming to the cross roads. For someone who grew up on the beach, out there seemed like the most remote place in the world. The stop sign was peppered with bullets. My dad didn’t even brake—he just raised his arms and yelled “rolling stop” as we blew right through it.

There were, I remember, four to six trailers at this intersection. They encircled a large, steel-beam radio tower that you could see for miles. Aside from the laundry drying outside, the trailers looked abandoned. I wondered why anyone would live there, and so close to a radio tower. It had been an obsession growing up, these freakish people committing horrible atrocities inside. But why that? Why not thoughts of more? More money; a bigger promotion? I thought of that as I drove toward the tower. The tenacious strive toward success. It was always just out of reach. I killed the engine before the stop sign. The fields were barren now, and stretched into the distance in each direction.

I was in insurance when the government began scaling back the economy. A few folks saw it coming. Our company sold all the ergonomically designed chairs and installed coin operated locks on the bathroom stalls. They traded my BMW company car for a Chinese sedan. They did, however, let me keep my company girlfriend, who was specifically designed to “enhance” my lifestyle: She was prone to debt, prescription drug-induced crying jags, and had breasts engineered to near perfection.

Thus did consumerism and procreation go hand in hand.

Field dwellers didn’t have breast implants or bald pubic regions. These things had nothing to do with survival. Daily life revolved around the radio tower, or rather, what the tower provided. Grandma had an aluminum hip that intercepted phone calls late at night. Like I said, politicians and pornographers could afford to speak in whole sentences, and did so in great detail about anything they pleased. Overhearing an educated conversation like that would have cost five thousand dollars. That’s how much it cost to ‘unlock’ this particular radio channel. Even the rich weren’t granted total privacy. When the signal wasn’t great, we’d stick our ear directly against Grandma’s hip. This minimized the "tinny" sound so we could hear more clearly.

A low, steady hum was always present around the tower. The trailers would sometimes vibrate, but it didn’t vibrate people so much as it permeated them. We all sat in plastic lawn chairs in the back yard. Every meal was barbequed on an open pit, and little Joey would run barefoot from one trailer to the next.

“Momma says ‘the hummin’ is God talking to Himself while he’s doing his work.”

“Great Joey,” I’d say. “Now run over and fetch me a jar of moonshine.”

It was still strange to me, hearing folks talk about God. Aside from OMG, which was changed from Oh My God to Oh My Gosh, talking about God beyond the context of Freedom was forbidden and taxable. The pornographers discussed ways to implement God into film plots, but this was done subtly, usually by symbolism, since no one understood big words anymore. For most folks, acronyms were cheaper and conveyed most thoughts.

“God microwaves our home with his love and hummin’ powers.”

“Did your momma tell you that, Joey?”

When asked a question, Joey would sometimes gaze up to the red blinking light. I had no idea he was looking up there for guidance.

“I think about hummin’ and how come other places don’t hum.”

“How do you know other places don’t hum?” I said.

“Well…look at you. I beg your pardon, but you’re dumber than a stump.”

It was true. Aside from my 30 years of life experience, I was no smarter than this child. At ten years old, he rebuilt the carburetor in my Chinese sedan. He could kill, pluck and gut a chicken in 4 minutes flat. He even knew how to brew moonshine using an old copper milk can. He’d mix in the corn and water and whatever else, pausing every so often to gaze up at the tower.

**